How to Read Comics #3: A Guest in the House

Analyzing what makes E.M. Carroll’s A Guest in the House so special.

Howdy, friend.

It’s October, my favorite month, and nearing Halloween, my favorite holiday. Each fall I meticulously track the weather and plan out my first fall outfit of the year in anticipation of the first real cold front. Silly, maybe, but I’ve always found refuge from my body dysmorphia in layering clothes, and I take the planning of this first outfit very seriously.

Over on my Instagram, I commemorated this year’s outfit with a sketch:

Anyway, in honor of this spooky season, I thought it would be apt to explore a graphic novel I’ve been thinking about since I picked it up a few months ago: E.M. Carroll’s haunting (and hauntingly brilliant) A Guest in the House. As I did in previous “How to Read Comics” installments (here, here, and here), I aim to introduce you to this incredible comic work and analyze what makes it so great.

If this is your first time visiting How to Draw, a hearty welcome. You can check out our archive here. And if you haven’t already, please consider subscribing so you don’t miss a thing.

Enjoy the crisp weather, if you’re able. ♡

– RJR

“I don’t sleep for days after seeing her. And when I finally do, my dreams are tangled, dripping things.”

―Emily Carroll, A Guest in the House

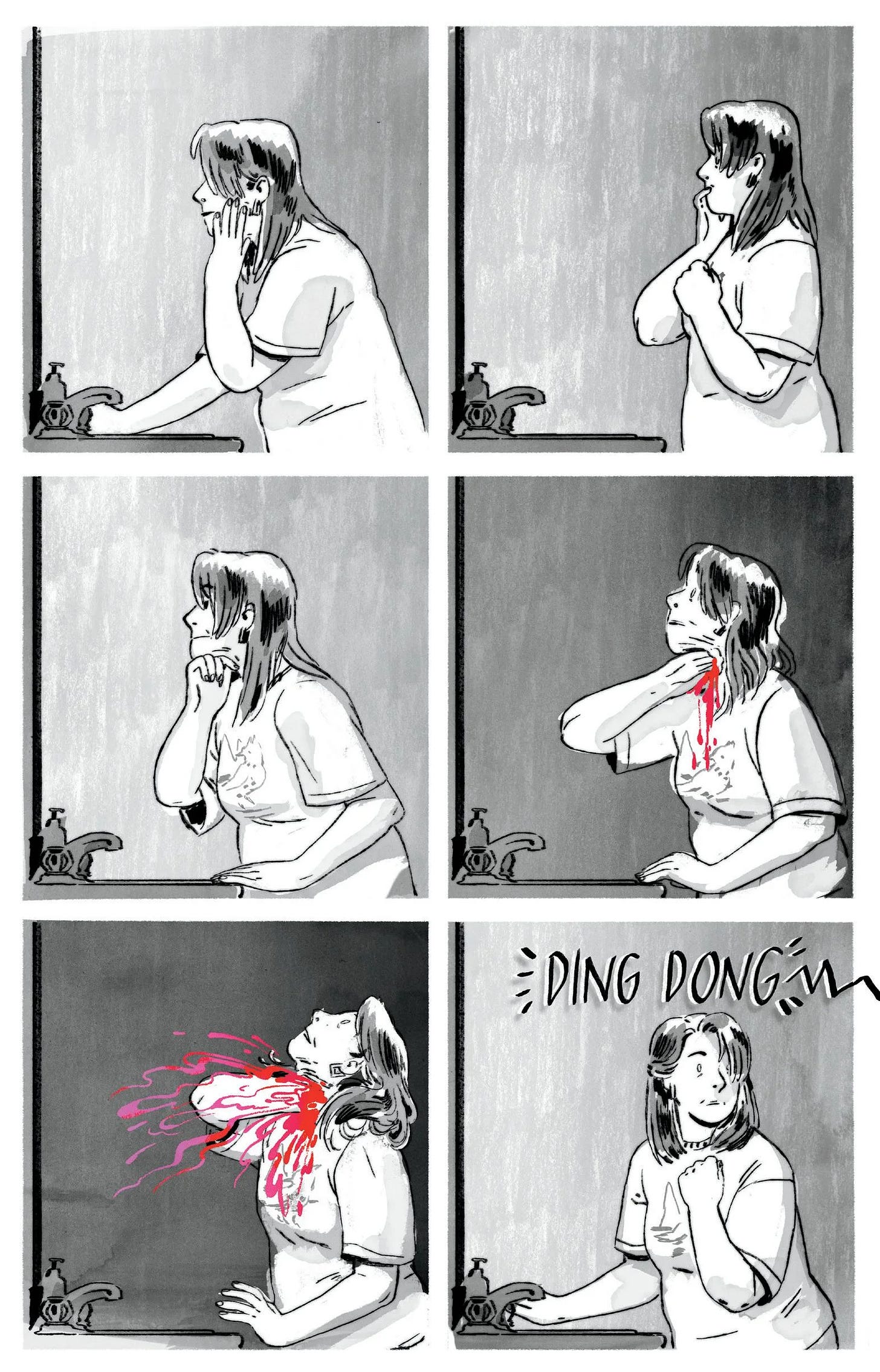

Published in 2023 and winner of both the 2024 LA Times Book Prize and the 2024 Lammy Award for LGBTQ+ Comic, A Guest in the House by E.M. Carroll follows Abby, a recently married woman whose grief and suspicion intensify as she begins to uncover dark secrets about her new husband and his deceased first wife. This book masterfully balances a restrained narrative—which I’m mostly keeping hush-hush here, as it’s best to read with little/no prior knowledge—with moments of striking intensity. Carroll uses limited color palettes throughout much of the book to reflect the monotony of Abby’s life, only to interrupt this with vibrant hues emphasizing key emotional and narrative turning points. At its core, the story explores themes of grief, loss, and isolation, showing how the past can haunt the present, both figuratively and literally, through Abby’s deeply unsettling experiences in her new home.

While the colors and illustrative work are a draw, it’s Carroll’s masterful use of space and flow—pushing against traditional ideas of how a graphic novel should look, feel, and be read—that make this read like nothing I’ve experienced before in a comic work.

Let me explain. Over the past year and a half of this Substack’s existence, I’ve often discussed the importance of panels in comics. As creators, panels are how we direct the narrative and imbue a scene with emotion, pacing, and meaning.

Consider these two panels from Charles Burns’ newest book, Final Cut:

In film speak, we’d call this a shot/reverse shot—a technique that cuts between two different camera angles to show multiple perspectives, dialogues, etc. In these two panels, this choice to show our antagonist, Brian, up close and then in a reflection helps reinforce his detachment from reality. It also slows the pacing down, allowing us to linger on his face, his distortion in the toaster, his words.

Panels are the frames through which readers experience the story, and how we arrange them dictates everything from the flow of time to the intensity of a moment. So what happens when we’re dealing with a comic that relishes playing outside these expected bounds?

The visual progression/narrative pacing of A Guest in the House is so strikingly unique from anything I’ve read before, that I immediately reread the book to ensure I hadn’t missed anything. To be clear, this book does read like a traditional graphic novel at times (read: there are panels), but much of the book’s power comes from Carroll’s use of full-page images and layered compositions (and, in many of these instances, a sudden burst of vibrant color that causes us to step back and take notice). At times, multiple images overlap, crowding the page, just as Abby's emotions and experiences crowd her mind. This unique approach immerses the reader in Abby's fragmented, disjointed world.

Here, at the start of the book, Abby narrates her seemingly contented domestic life. The flow from one chore to the next, presented in a slightly jumbled manner, mirrors the natural rhythm of her day—mundane yet quietly unsettling, setting the stage for the unraveling to come.

It makes sense. She’s trying to convince herself—and us—how blissful her life is. There’s no time for a breath that a panel would bring. Later, a single panel conveys the suffocating feel of that same domesticity, as a pesky neighbor visits and quite literally pushes Abby out of her own story.

And here, panels are used to help reinforce Abby feeling boxed in by her life and “duties.”

What sets this book apart is the way it breaks from traditional narrative conventions, allowing the art to flourish in ways that wouldn't otherwise be possible.

Take, for example, these two panels with their storybook-like approach. In my opinion, they are not only more engrossing and immersive than they’d be as a series of traditional panels, but they also make us feel as though we are part of the unfolding narrative by forcing us to inspect, and then inspect again.

By moving beyond the traditional use of panels at key points, the book creates a sense of freedom in storytelling, offering an experience that transcends strict visual boundaries. This enhances the emotional impact, as borderless pages allow the art to feel more atmospheric, building mood and tension without constraints. Most importantly, it encourages visual creativity, enabling Carroll to blend images and text in more expressive, dynamic ways.

Look: Not every book needs to look like A Guest in the House. Abby's narrative demands that we sometimes break free from panels, allowing the art to overwhelm and take center stage. It does so intentionally, always in service of the story. While panels are essential tools for many creators to advance their stories, E.M. Carroll pushes the boundaries of what the comic medium can achieve. Just as Will Eisner’s A Contract with God, Art Spiegelman’s Maus, and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis (and so many other graphic novels) reshaped how we view comics as art, Carroll gives us a glimpse of where the medium may go next.