How to Draw (Meaning)

Unpacking meaning-making in comics—what we say without saying and how we build between the lines. Plus: Lynda Barry, the surreal work of Marc-Antoine Mathieu, hex #EFDACC, and more.

Howdy, friend.

While meaning is a broad term, I see this as the third piece in a kind of informal series—after exploring movement and stillness—now asking: How do we derive meaning from comics? What even counts as narrative? And what happens when we push back against traditional storytelling?

Lately, as I revise drafts of my graphic memoir HARD BODY, I’ve found myself stripping out more and more text—learning to trust the images to carry the weight. What happens when I stop narrating every beat? When I let the space between panels do the work? The more I pull back, the more I realize how much comics rely on inference—how much we, as readers, intuit and assemble. It’s a kind of narrative alchemy unique to this form.

So, this month I want to look at how comics create meaning—even when they withhold. We’ll start with pages that reduce elements to their barest bones while still delivering a story, and then move toward works that bend or even resist narrative altogether.

If this is your first time visiting How to Draw, a hearty welcome. You can check out our archive here. And if you haven’t already, please consider subscribing so you don’t miss a thing.

Spring has sprung here in Nebraska. Hope you’re enjoying the new smells as much as I am. ♡

– RJR

The graphic novel is already too restrictive a definition for me. I would rather speak of graphic literature, which encompasses much more broadly the field of artistic expression of what a certain comic strip has become today. Why limit ourselves to the "novel"? We must also take into account essays, poetry, short stories, newspapers... All genres increasingly invested by comic strip authors.

―Marc-Antoine Mathieu, speaking with The French Institute in Chin

What is the nature of a comic? What is a comic supposed to do—what happens when it defies expectations?

In past newsletters, I’ve explored the mechanics of comics—how narrative takes shape through the interplay of panels, gutters, dialogue, captions, layout, linework, rhythm, etc. Comics are a choreography of these elements working together to create a story that’s both seen and felt. This is the narrative, and from it our comic works derive meaning.

But what if meaning doesn’t come from that choreography at all? What if it comes from what’s missing—or what resists being named? What happens when comics strip away the tools we’ve come to rely on: text, clear narrative, even a coherent visual structure? What does it mean to draw meaning when so much of it is left unsaid?

Many comics contain moments where the narrative text falls away. While the union of image and text is a hallmark of the medium, removing the text does something radical: it shifts the burden of interpretation onto the reader. Without the guidance of narration or dialogue, we’re asked to assemble meaning ourselves—not through instruction, but through intuition. Meaning becomes something you search for, not something you're handed.

Take, for instance, this incredible page from R. Kikuo Johnson’s No One Else.

Set in Maui, No One Else follows Charlene, a nurse and single mother, as she cares for her young son and aging father—all while trying to stay afloat. Here, after a particularly harrowing event, Johnson gives us a sequence of six silent panels. It’s a well-earned stillness, a pause that lets the emotional weight settle. Like shots in a film, these images invite us to assemble meaning on our own: the wind has quieted, the sun is setting, and for a brief moment, everything feels as it should be.

In my graphic memoir, HARD BODY, I often turn to textless panels or pages to underscore meaning in a similar way.

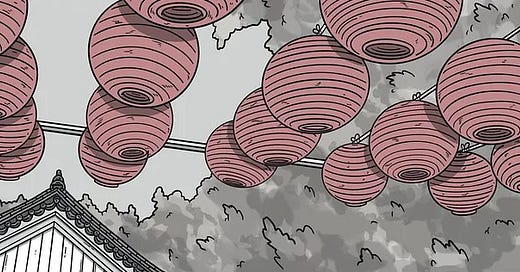

This two-page spread originally included narrative text—not just in the white spaces, but within the panels themselves. At this point in the story, I’m reaching for solace, for a connection to the natural world. Ultimately, stripping away the words felt truer. The empty spaces, once filled with narration, now offer a quiet that mirrors my inner state—a visual echo of visiting temples in South Korea. Rather than explaining how I got there or detailing what I did, the silence invites a deeper, more reflective understanding.

Consider flipping this sentence: Comics-makers challenge the form itself by leaning into inference and quietly relying on the reader. In comics theory, we often distinguish between diegetic space—what is directly shown on the page—and non-diegetic space—what lives in the gaps, especially in the gutters between panels. If we see a character wake up in one panel and then eating breakfast in the next, we don’t need the intermediate steps—we fill them in ourselves. We assume the brushing of teeth, the walk to the kitchen, the opening of a fridge. Those moments vanish, but our minds still carry them. In that space, something remarkable happens: the reader becomes a co-author. Meaning is not just received—it’s built.

Some comics push this even further, testing how much can be stripped away from the traditional form while still delivering meaning. Chris Ware’s work often resembles architectural schematics more than conventional comic pages. He layers diagrams, infographics, nested timelines, and recursive layouts—but beneath all that formal precision, a deeply human story quietly unfolds. Ware doesn’t reject narrative; he conceals it, asking the reader to unearth it.

Consider this page from Building Stories, and all the ways it invites us to construct meaning.

Lynda Barry’s What It Is isn’t a comic in the typical sense—it’s more like a visual essay, dream journal, and teaching manual all collaged together. There are speech bubbles and characters, yes, but there are also grocery lists, childhood photos, scribbled memories, questions about the subconscious, and deep meditations on the image itself. Barry doesn’t tell a story so much as she invites a dialogue—with the reader, with herself, with her childhood. The page becomes a site of excavation, not instruction.

Rather than presenting meaning, Barry asks us to generate it. Her panels are messy, layered, nonlinear. A single page might contain three different voices: a memory, a quote, a cartoon, all colliding. But in that mess is the point—Barry is showing that our inner lives aren’t clean narratives. She defies the form not to confuse us, but to reach something truer: that meaning is something we make, not something we’re given.

But what happens when a comic removes narrative altogether?

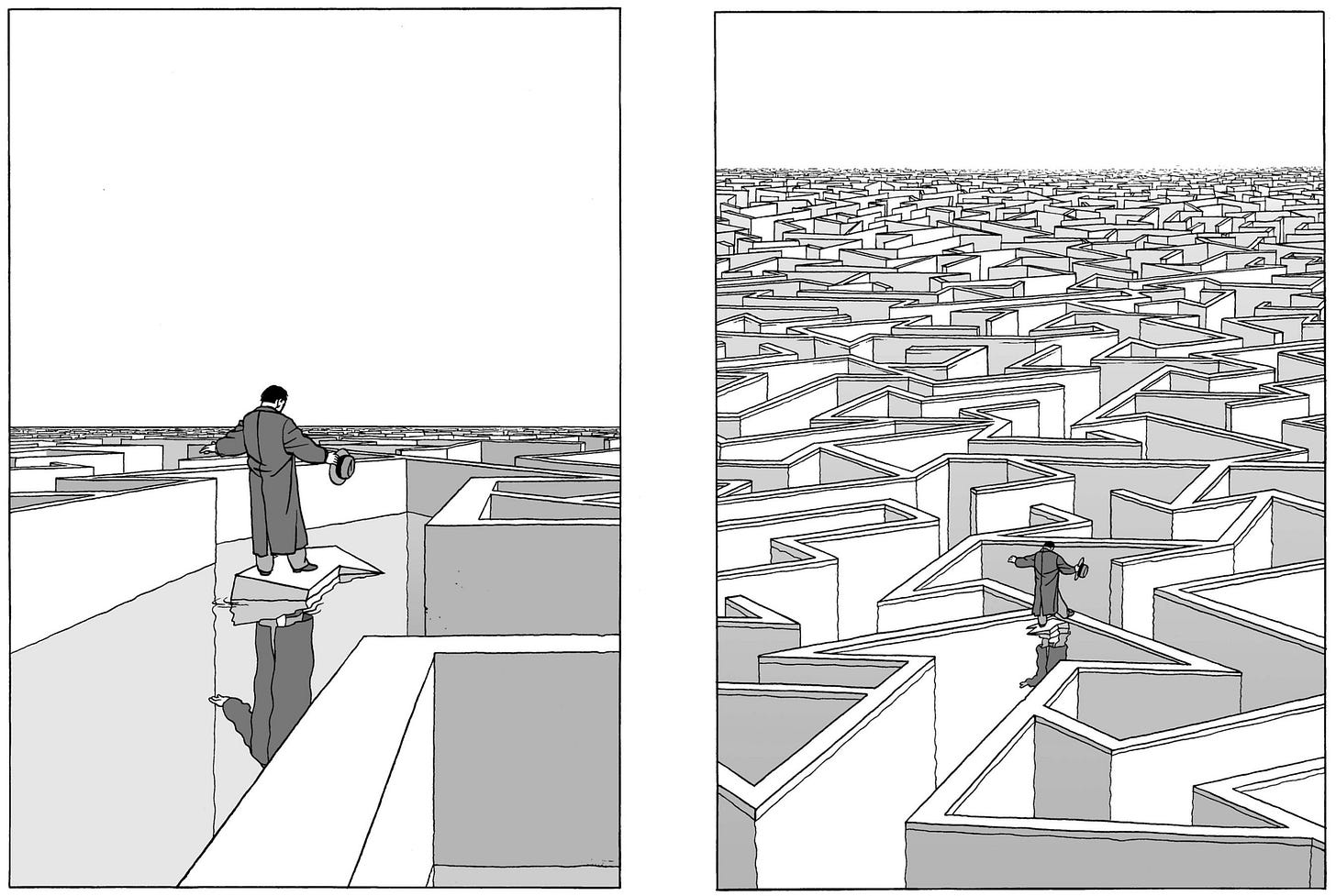

Take Sens by Marc-Antoine Mathieu: a book with no dialogue, no captions, no conventional plot. A lone figure moves through an abstract landscape, guided only by arrows. There is movement, but no clear goal. Meaning here isn’t just subtle—it’s elusive and, you could argue, doesn’t reveal itself at all. The book becomes a kind of philosophical mirror, reflecting back whatever the reader brings. It's not about reading a story. It's about sitting with ambiguity.

So when does a comic stop being a comic? And, maybe more importantly, what do we gain by letting go of certainty, by drawing meaning where none is given?

As comicsmakers, we have to be willing to reach beyond the traditional and expected. We work in a form built on the tension between image and text, between what is shown and what is left unsaid. That tension is where meaning lives.

In the end, making meaning in comics often comes down to this:

When do we tell the reader something has happened?

When do we show it instead?

Or, because I love me an analogy: When do we provide a ladder to the roof, and when do we trust the reader to find their own way up?

The beauty of comics—especially those that stretch the form—is that meaning isn’t always handed over. It’s uncovered. Pieced together. Felt.

That’s the work. That’s the invitation.

What I’m reading:

Nonfiction: Serial Selves: Identity and Representation in Autobiographical Comics by Frederik Byrn Køhlert

Fiction: Bear County, Michigan by John Counts

Graphic: Ocultos by Laura Pérez

Graphic: Guerillas: Omnibus Edition by Brahm Revel

Graphic: Our Little Kitchen by Jillian Tamaki

Graphic: Ephemera by Briana Loewinsohn

A perfect panel:

Ocultos by Laura Pérez

The color I’m obsessed with right now:

hex #EFDACC– “Almond”

I appreciate this as I think about making new work.

always interesting and thought provoking - lots to learn - thanks! You obviously put a lot of work and thought into your posts. Thanks.