How to Draw (Hope)

The transformative power of comics and how they connect us to something greater. Plus: Mark Rothko and Agnes Martin, Art Spiegelman's Maus, hex #784560, and more.

Howdy, friend.

In last month’s (brief) newsletter, I reflected on the power of the word despite:

Despite. I love this word. A pause in action. A consideration of how to push forward or fight back. A revolution in seven letters.

Since then, I’ve been thinking about the role of art when we’re scared—when the world feels like it’s closing in; when decency, empathy, and kindness seem on the chopping block. We’ve all heard someone say, “Hope matters now more than ever!” but what does that mean? How do we glean hope from art—comics, especially? This month, I’m exploring how comics can help us find hope, why creating matters even when things are bad, and how documenting my past through graphic memoir has helped me heal in ways I couldn’t have imagined.

Let me also say: What a year it’s been! I deeply appreciate everyone who reads my newsletter—even the long ones—and finds something meaningful in these posts. I’d still write this if it felt like shouting into a void, but knowing there are folks on the other end of the echo means the world to me.

If this is your first time visiting How to Draw, a hearty welcome. You can check out our archive here. And if you haven’t already, please consider subscribing so you don’t miss a thing.

Happy holidays to you and yours. See you in 2025. ♡

– RJR

“Hope locates itself in the premises that we don’t know what will happen and that in the spaciousness of uncertainty is room to act. When you recognise uncertainty, you recognise that you may be able to influence the outcomes—you alone or you in concert with a few dozen or several million others.”

—Rebecca Solnit

How do you draw hope? What is the role of art in sustaining it?

Last month, millions of Americans watched the possibility of a more united, humane path forward crumble. For many, the election results brought instant fear: fear for ourselves and those we hold dear. Sadness quickly turned to anger, and for some, a sense of abject defeat. How do we preach love and compassion in moments like these?

When we’re down, we often turn to a familiar refrain to help us endure: Art—and the act of creating it—matters now more than ever.

But why does it matter? No, more than that: How does it inspire? When the world feels like it’s on fire, why do we come back, again and again, to this belief?

For me, it comes down to two key points:

Art serves as a reminder of our shared history.

Art reflects the complexities of the human experience.

In times of crisis, I find myself returning to the works of two artists who resonate deeply with me: Mark Rothko and Agnes Martin.

Rothko, a Latvian-American painter, is celebrated for his large-scale abstract compositions that delve into emotional depth through fields of color—a style he pioneered. Even if you think you haven’t seen a Rothko, chances are, you have. His work is ubiquitous and, for many, misunderstood, often invoking the refrain: “It’s just colors on a canvas. Anyone could do that.”

However, Rothko’s paintings are far more than they seem.

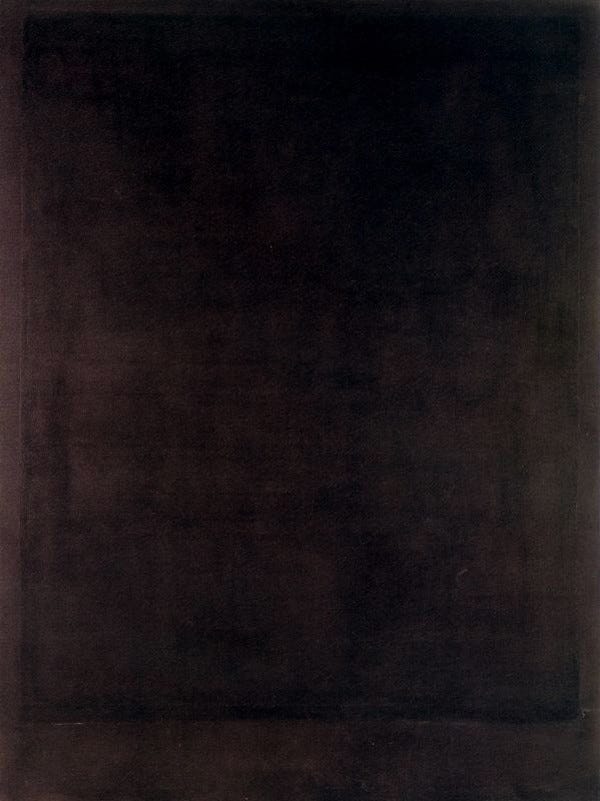

Take, for example, one of the works from the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas—a non-denominational space that serves both as a place of worship and a monumental art installation. The chapel features 14 monumental dark-hued pieces created between 1964 and 1967, each inviting contemplation and evoking a profound sense of presence.

This is not merely slabs of dark paint on a canvas. Rothko’s work, especially here in the chapel, invites viewers to experience it slowly. The colors shift and change with the overhead light—the only illumination in the space comes from a window in the ceiling. There’s a quiet intensity. While the work may seem stark or minimal at first glance, a closer look reveals layers of variations and subtle changes in hue and texture.

And while viewing any of Rothko’s work on a computer/phone screen admittedly flattens the experience, up close and in person these are pulsating works that draw you in, inviting a deep reflection of the self.

Agnes Martin was an American abstract painter celebrated for her serene, minimalist grid and stripe paintings. Her work explores themes of inner peace, spirituality, and the pursuit of beauty through subtle repetition and restraint.

Like Rothko, Martin’s work might, at first glance, seem “easily replicable.” But it’s so much more than grids, lines, and portioned-out color.

Look at her 1963 painting Night Sea.

Like Rothko, I’m drawn to Martin’s work because it invites a sense of serenity and introspection. The soft, hand-drawn lines evoke the rhythm and expanse of the eponymous sea at night. The longer we look, the more the grid seems to dissolve, our eyes drifting across the work. There’s a delicate interplay between structure and infinity. We feel this piece—we are encouraged to feel rather than interpret it.

Both Rothko’s and Martin’s works offer a way to retreat and reflect, especially in times of hardship. To be lost in their stillness, or to find a path forward in their subtle movement, allows us to exist in both spaces. And perhaps that’s what we mean when we talk about the necessity of art: In the end, art inspires hope by creating space for introspection, healing, and connection to something greater than the self.

While these particular works might not speak directly to any sort of shared history, they still prompt us to reflect on our lives and the broader human condition. This is the power of non-representational art: It doesn't dictate what to think or feel but invites us to probe deeper, offering a kind of "blank canvas" for personal interpretation.

Okay, so what about comics?

While comics may not always offer quite the same simplicity-cum-introspection that Rothko and Martin do in their works (although, sometimes they do), the interplay of text and images can open doors to complex emotions and reflection. By depicting characters navigating struggles or finding moments of peace, comics can offer readers a quiet sense of understanding and solidarity. Additionally, the visual sequencing of comics allows for pause moments—silent panels or images that encourage introspection, inviting readers to stop, breathe, and internalize the message.

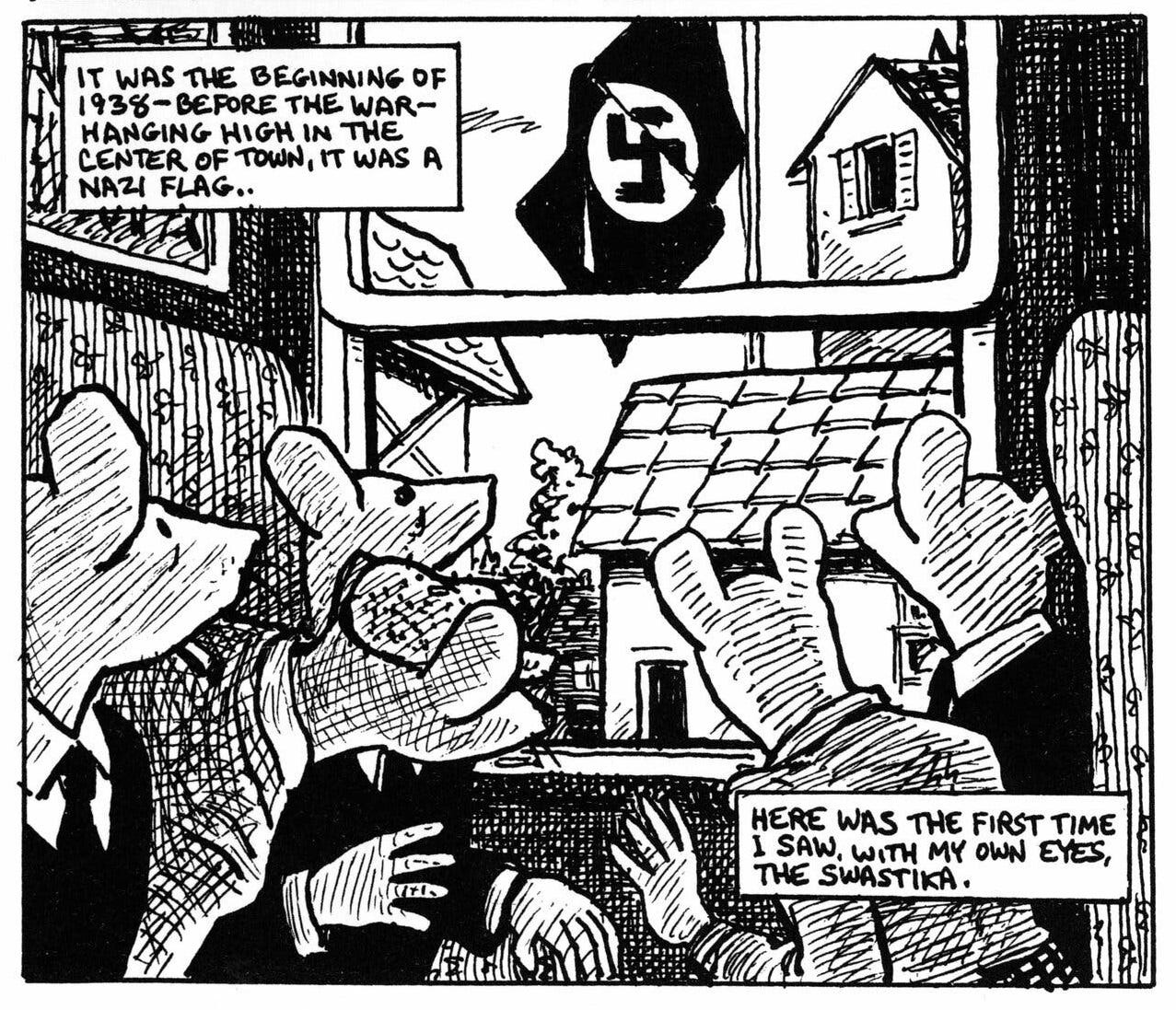

Let’s consider Art Spiegelman’s seminal graphic novel, Maus.

Maus uses anthropomorphic characters—Jews as mice, Nazis as cats—to tell the story of the Holocaust through the experiences of Vladek Spiegelman, a Jewish survivor, and his son, the author. This choice enhances the symbolic power of the story, highlighting the predator-prey dynamic between Nazis and Jews in a universally recognizable and visually striking way. This allegorical approach creates a distance that allows readers to engage with the trauma of history, making it emotionally impactful and more accessible without the heaviness of direct human representation.

Despite the trauma Vladek Spiegelman endured during the Holocaust, recounting his story reminds us of the importance of remembering and sharing personal histories. Through this act, Spiegelman not only honors his father’s survival but also confronts his own struggles with guilt, showing that grappling with painful histories can be a step toward healing.

Perhaps drawing hope is, to some extent, about drawing truth—recounting and documenting our histories to remember what we fight for. Graphic novels and comics make these narratives accessible to all ages, with moments where the art itself invites us to pause, reflect, and reconsider.

Let’s explore a few other examples.

George Takei’s They Called Us Enemy (illustrated by Harmony Becker) recounts his childhood experiences in Japanese American internment camps during World War II. Like Maus, this combination of personal narrative and historical record explores themes of identity, injustice, and resilience; this narrative reminds us of the importance of acknowledging painful histories and the strength that can emerge from sharing them, just as in Spiegelman’s work.

The Best We Could Do by Thi Bui chronicles her family’s escape from Vietnam during the Fall of Saigon and their resettlement in the United States, exploring the complexities of immigration, identity, and the generational trauma that comes with war and displacement. Bui gives voice to the often overlooked experiences of refugees, shedding light on the emotional cost of leaving one’s homeland while also highlighting the resilience of those who rebuild their lives in the face of such loss.

Joe Sacco's Palestine is a groundbreaking graphic novel offering a journalistic, firsthand account of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Through Sacco’s experiences in the West Bank and Gaza Strip in the late 1980s, he interviews Palestinians living under occupation, capturing their stories of hardship, displacement, and resilience; this book not only documents personal narratives but also reflects on the complexities of the conflict, helping us better understand the human toll of an ongoing struggle.

Each of these works showcases how comics can tackle serious, real-world issues with both depth and empathy.

Working on my graphic memoir Hard Body has shown me just how healing the process of creating—and then confronting my life so starkly on the page—can be. Memoir isn’t about painting over the past or covering it up, it’s about laying yourself bare, messy, ugly bits and all. By revisiting these traumas (and Traumas), we remember how far we’ve come, that we’re not alone, and that even in our darkest times, there’s a path forward.

Hope in Hard Body comes from revisiting painful memories—not to tie them up neatly, but to remind myself of:

My complicity in past breakups and how my toxic behaviors led to recurring patterns I couldn’t see or break free from for years.

The sage advice and attentive presence of a now-passed-on family member whose words meant more to me than he ever knew.

My evolving relationship with the natural world—understanding the space I occupy in it, the timeline of human history, and how that perspective helps me face my fears and approach each day anew.

Asking questions like Why does art matter? and How does art inspire hope? gets us to the same conclusion: Art helps us see. It keeps us from being alone. When we are alone, we’re afraid. And when we’re ignorant—when we can’t see—we end up repeating the mistakes of the past, doomed to a hopeless existence. We continue making art—comics and all—to remind ourselves and those around us what we’re fighting for, that there’s always some path forward.

Hope is a great remembering.

What I’m reading:

Nonfiction: An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

Poetry: Render: An Apocalypse by Rebecca Gayle Howell

Graphic: Advocate by Eddie Ahn

Graphic: Final Cut by Charles Burns

Graphic: A Contract with God by Will Eisner

Graphic: Summer Blonde by Adrian Tomine

Graphic: Cats of the Louvre by Taiyo Matsumoto

Graphic: Why Art? by Eleanor Davis

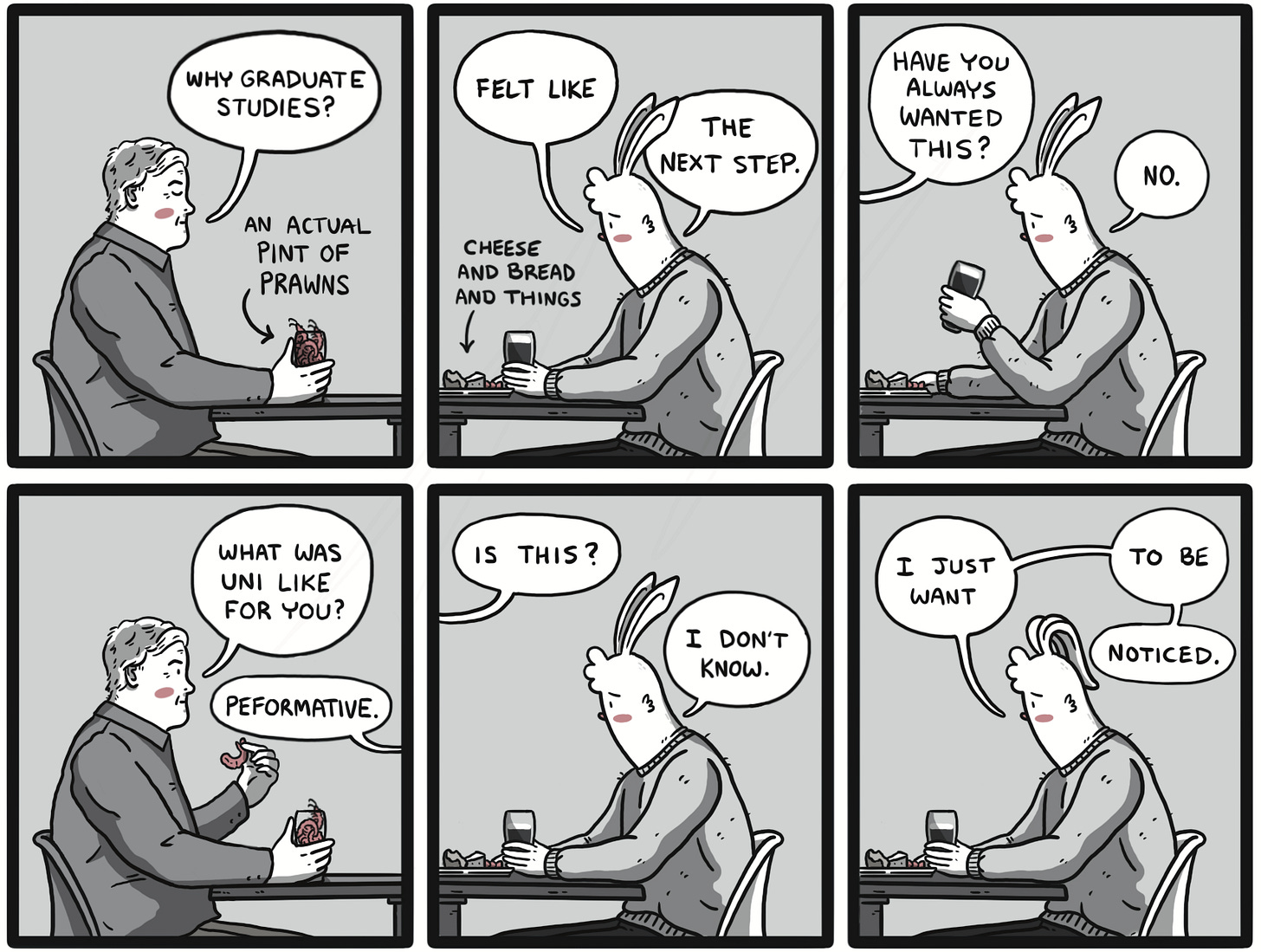

A perfect panel:

Final Cut by Charles Burns

The color I’m obsessed with right now:

hex #784560 – “Cosmic”

News:

I’m delighted to share my second cover for Great Plains Quarterly. This piece was inspired by a visit to western Nebraska, where I saw a man riding a horse through the center of a small downtown—seemingly just part of an ordinary day. I’m not from the “city” by any means, but this was a level of “country” I’d never encountered before. I’m thrilled with how it turned out.

“We feel this piece—we are encouraged to feel rather than interpret it.

Both Rothko’s and Martin’s works offer a way to retreat and reflect, especially in times of hardship. To be lost in their stillness, or to find a path forward in their subtle movement, allows us to exist in both spaces.”

Thank you for taking the time to share all of this. I’ll be thinking on it all for a while. (Also I’ve read Takei’s children’s book about his time in the internment camps but never the one you mention… Will have to check it out!)

I really enjoyed this post. Wonderful thoughts!