How to Draw (Collective Fury): An Interview with Aubrey Hirsch

Aubrey Hirsch chats about her upcoming book Graphic Rage, the emotional force of comics, embracing imperfection, and more.

Howdy, friend.

Here’s something I’ve been noodling on lately: How do we make art that reckons with the world’s heaviness—rage, injustice, the daily grind of inequity—and still hold space for hope? For change? For humor?

Enter

.I’ve followed Aubrey’s work for a while now, and her comics never miss. They’re razor-sharp, deeply personal, and deceptively approachable—what she calls the “spoonful of sugar” model. She also produces incredible work on her Substack, which you should absolutely subscribe to.

Her new book, Graphic Rage: Comics on Gender, Justice and Life as a Woman in America, is out this October from Split Lip Press and collects twenty-five of her sharpest, most searing comics, which you can pre-order now. And given everything going on in America right now, this book feels especially prescient.

So, I wanted to talk to Aubrey about how she approaches this balance—how she turns fury into clarity, how she keeps creating through burnout and broken systems, and how she’s learned to embrace imperfection along the way.

If this is your first time visiting How to Draw, a hearty welcome. You can check out our archive here. And if you haven’t already, please consider subscribing so you don’t miss a thing.

Be well. ♡

– RJR

The following interview took place in May 2025.

Robert James Russell: You come from a background in prose—fiction, essays, more “traditional” writing. How did visual storytelling come into your practice? Was it always there, or did something shift?

Aubrey Hirsch: It was definitely an unexpected hard left turn. I always considered myself primarily a fiction writer, and I was teaching fiction writing when I started noticing comics popping up in literary journals. It was very exciting to me because it looked like a lot more fun than what I was doing—I just hadn’t realized we were allowed to do that! So I decided to try making comics. 8,000 hours of YouTube tutorials later, here we are!

RJR: Your comics walk the line between personal narrative and cultural critique—something that’s become a hallmark of your work. What does the comics form let you do that prose alone can’t? How do you think it helps you translate complex ideas—like systemic injustice or economic policy—into something more immediate and emotionally resonant?

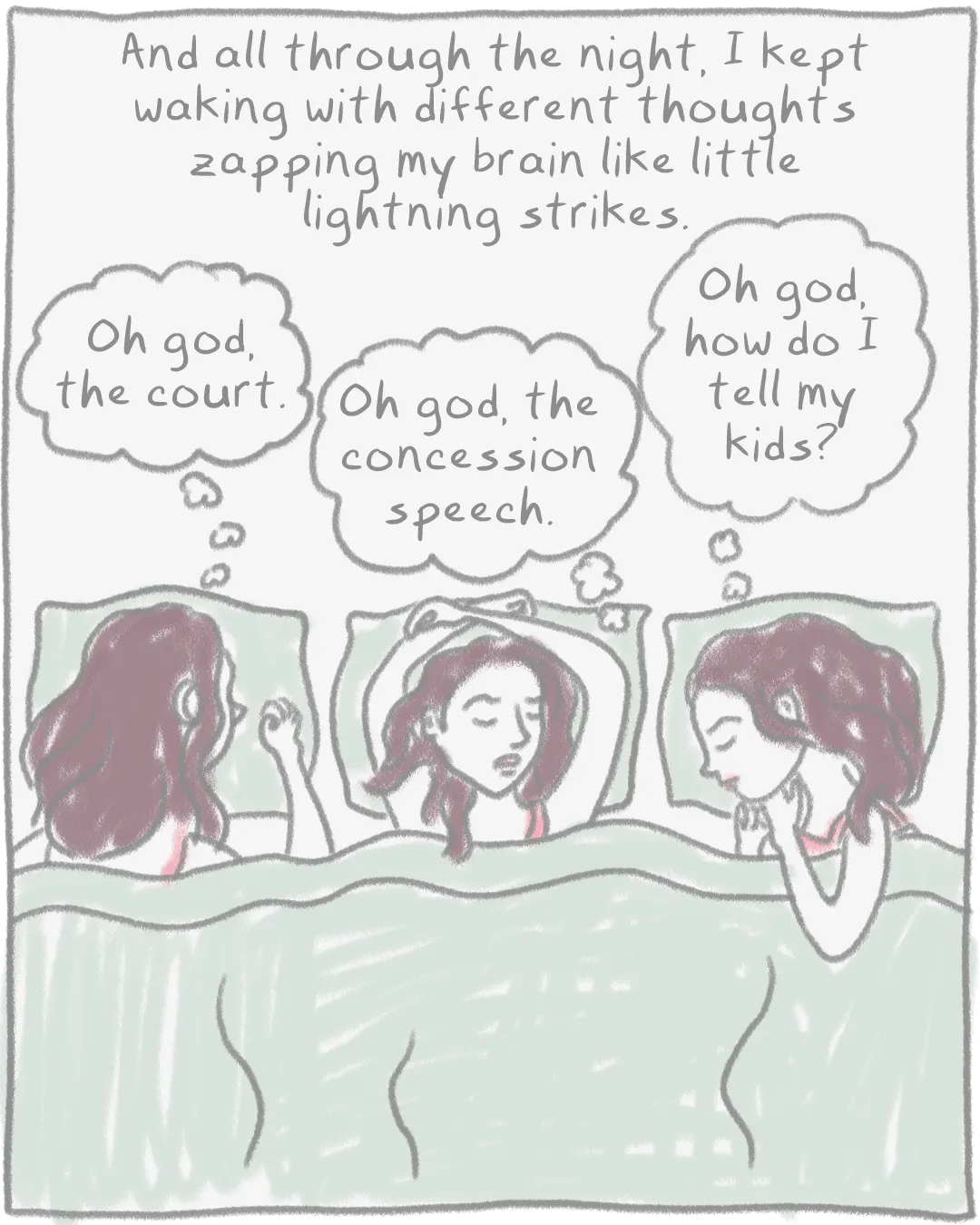

AH: The superpower of comics is that they make everything, even really complicated concepts, feel accessible. I think I can get more people to pay attention to something really complex, or tough, or just difficult to stomach, because I can say, “Look! Pretty pictures!” I call it the “spoonful of sugar” model of comics journalism. I also love the way words and images can work together to create additional layers of meaning. An image can add emotional context to a dry set of facts or illuminate data in a way that words alone can’t. There’s something really powerful about not just saying, “Women carry the majority of the mental load around keeping family connections,” but also being able to visually represent just how disproportionate it is.

RJR: What’s your process like for creating your comics—are you working analog, digital, or some combination? Has your workflow changed as your visual style has evolved?

AH: When I first started, I did all my linework on paper and added color, text, and panel borders digitally. Once I got my first real check from a comic I sold, I bought myself a drawing monitor, and now I do everything start-to-finish in Photoshop. I really rely on Control + Z when I’m making art!

My process has definitely become more streamlined as I’ve become more comfortable with the form. The research is still the part that takes the most time. Then I generally script and thumbnail as one step. Making the final art is my favorite part of the process because, if I trust my script, I can just relax, listen to podcasts, and draw. I’m still new enough to the art side of things that there’s an element of experimentation and discovery in each piece. Every time I make something, I learn something new!

RJR: Graphic Rage covers a wide range of topics—like abortion rights, economic injustice, and the politics of motherhood. What helped you determine which stories belonged in this collection?

AH: That was very difficult! I was lucky to have help from some great editors, Michael Trager, Kristine Langley Mahler, and my partner Ben, in narrowing down the contents of Graphic Rage. We started by looking at all of the work I’d produced that felt in line with the book’s theme. Then we eliminated some with discordant art styles, or pieces that felt outdated (I had some pieces on Covid, for example, that I’m still proud of, but we felt the moment for them had passed). The last pass came after organizing the book into its final order. Any pieces that didn’t seem to fit neatly into one of the four sections, sadly, got left behind.

RJR: A lot of your work lives at the intersection of vulnerability and anger. How do you manage the emotional demands of making work that is so personal, while also tapping into collective frustration?

AH: That’s such a perceptive question, but I would add something to it. I’m spending a lot of time right now as a person at the intersection of vulnerability and anger. But the space in which I can actually work is the intersection of vulnerability, anger, and hope. I really can only make art about something if I have at least a tiny bit of hope that it could do some good. And the collective frustration I feel around me is such a big part of that! My primary goal is always that my work will do something, whether that’s raising awareness of an issue, inspiring activism, or even just validating someone else’s anger with my own.

RJR: What kind of space—mental or otherwise—do you need to make this kind of work? And how do you know when something’s finished?

AH: Whew! If you had asked me this question five years ago, I would have had an entirely different answer. When Covid hit, my kids were out of school for a year and a half, and I was the person mainly in charge of homeschooling them and, you know, generally keeping them alive. I learned to work in 20-minute bursts with a second-grade math lesson playing via Zoom in the background. I used to be kind of precious about my creative environment, but that incredibly difficult time taught me that I really can work under almost any circumstances.

I’ve also learned to be less precious about feeling like things are “finished,” because nothing is ever really finished! I’ve learned not to let “perfect” be the enemy of “done,” and I’m getting braver about sharing work in a rawer state. I think there’s something special about art that feels less polished, less guarded, and more visceral. Now I think something is “finished” when I’m excited to share it, rather than when it’s “perfect.”

RJR: More literary journals and publishers seem interested in visual storytelling these days—not just comics-only outlets, but places that historically focused on text. Are you seeing that shift too? And how has it affected the way your work is received or published?

AH: This is such a great time for comics. I’ve had several editors reach out to me about working together and say something like, “We’ve never done comics before,” but the power of visual storytelling is becoming so mainstream that, I think, they don’t want to get left behind. When I made my first comics, I was just hoping to find homes for them in literary journals. I definitely never expected to be publishing in big media outlets like Vox, TIME, or The Washington Post. The wider movement toward more and more graphic essays and graphic journalism has been huge for me in finding an audience for my work.

RJR: What are your hopes for Graphic Rage—in terms of how it’s received, and how it contributes to or maybe even shifts the conversations we’re having around gender, justice, and the everyday experience of being a woman in America?

AH: The Midwestern millennial in me very much wants to say, “Oh, don’t mind me! I just did a thing.” But the truth is I worked really hard on this book, and I do hope people read it and like it! My hope is that by translating some of these issues into comics and putting my own spin on them, I can make people see them in a new way and maybe bring more people into the conversation. I hope the book finds readers who can learn from it, feel validated by it, and maybe even find some moments of comic relief amid the nightmare hellscape that is our country right now.

Thanks so much for these thoughtful questions!!

Thank you for this interview! It was very informative and inspiring. ❤️